When We See Us: Centering Black Art, Softness, and Self

On Black Art and Belonging

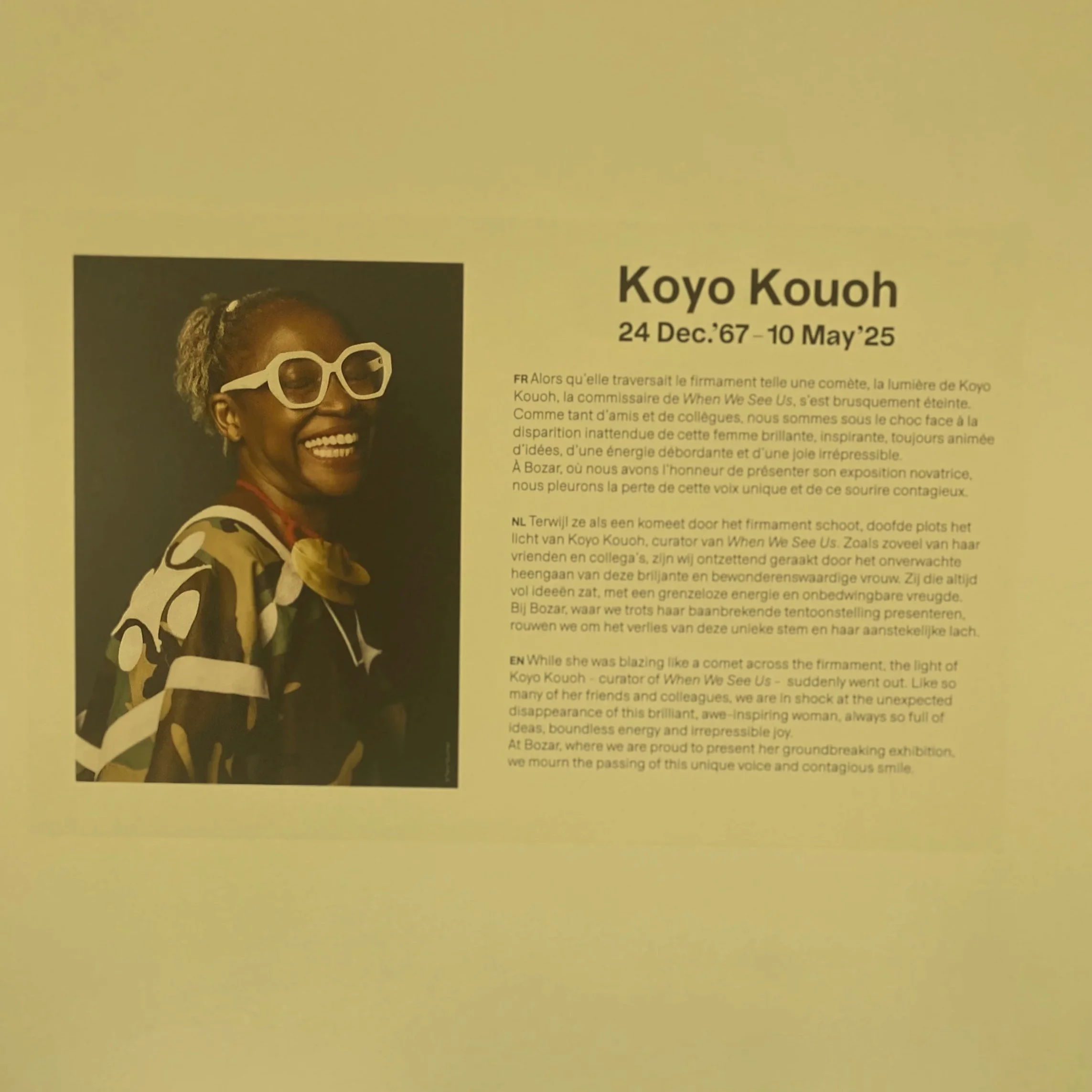

This morning, I took the Eurostar from Paris to Brussels. The reason was simple, but it had been sitting with me for a while I needed to see When We See Us. The exhibition had been on my list for months, and today, I finally made time for it. With Koyo Kouoh’s recent passing, it suddenly felt urgent, like an offering I had to receive in person, a tribute I needed to pay to a woman who changed the art world whether they were ready or not.

Bozar is a grand space, and the exhibition is sprawling. Over 150 works by Black artists from the continent, from the Caribbean, from the Americas. It spans the 20th and 21st centuries, and as soon as you walk in, you feel how much thought was given to atmosphere. There’s music, space to rest, softness built in. You’re meant to take your time. You’re meant to be in it, not just look at it.

And still, as I moved through these rooms, I found myself thinking: Who is this exhibition really for? Yes, it's a celebration of Black figuration, of Black life and creativity and interiority. But sometimes, even in these spaces, there's this subtle feeling: like we’re being looked at in amazement, as if people are surprised by our talent. Like oh, look what they can do. Like we’re still exceptional instead of simply being.

That tension never fully goes away.

I sat down for a while between works by Wangari Mathenge, Zandile Tshabalala, and Otis Kwame Kye Quaicoe. Vibrant color, beauty, presence—all kinds of bodies and genders, all kinds of intimacy. And as I sat there, I thought, I would love to be in the mind of a white person right now. Just to know what it feels like to walk into one of their institutions and not see themselves centered. Because that’s what this show does—it doesn’t apologize, it doesn’t explain. It centers us.

Reflection on Art, Absence, and Centering Ourselves

And the truth is, I know what it feels like to walk into museums and not see myself. I live in France. It’s a white country. I don’t expect to be reflected in its institutions, because they’ve never been ours. Even when our faces are on the walls, the framework often remains the same. But for a white viewer—especially one who assumes cultural centrality—When We See Us might be the first time they feel that quiet displacement.And maybe that discomfort is the beginning of something. A mirror they don’t recognize. A moment where they’re not the standard.

Now, they walk through their museum and they don’t see themselves. They’re not the default. They’re not the standard. And I wonder how that feels.

Because when I look around and see us—in all our shape, color, gender, vibrancy, I don’t feel lacking. I feel whole. But do they? Or do they feel displaced? Uncomfortable? Excluded? That question isn’t about guilt. It’s about understanding. Because for centuries, we’ve known that they didn’t see us as human. And we’ve learned how to live and create and love in spite of that. But what happens when they are the ones who aren’t seen?

For me, this visit wasn’t just about viewing artwork. It’s part of something I’m building. I study art, with a major in cinema. And right now, I’m trying to learn more about Black art, because in school, we don’t learn about it. We don’t get courses that focus on Black artists. It’s not in the curriculum, and it’s not normalized. And yet, it exists. It’s powerful. It’s vital. So I’ve started collecting—slowly—and trying to shape a language around it for myself.

There’s also this ongoing conversation about the term Black art. Some people resist it. They ask, Why label it like that? Shouldn’t it just be art? But to me, it’s not that simple. Black art as a term matters—especially within the diasporic context. Just like Islamic art or Indigenous art, it carries cultural, historical, and emotional weight. It isn’t limiting; it’s contextual. It places the work within a lived experience, a lineage, a shared memory. We can question the term—and we should—but we can’t deny its relevance. Not when the dominant framework has erased us for so long.

When We See Us is necessary. Not just because it brings Black artists into a major European institution, but because it centers us without flinching. It allows for softness and strength. For joy, for sensuality, for revelry, for spirituality like the 6 themes of the exibition. It doesn’t ask us to explain ourselves. It just lets us be.

And sitting there—surrounded by us—I felt something rare: seen, without having to perform. That alone is worth the trip.

Koyo Kouoh, in her lifetime, was adamant about pushing Black artists into the center of the global art conversation—not as a trend, but as part of the canon. Her curatorial legacy will live on in exhibitions like this one, which dare to take up space and dare to tell our stories on our own terms.

“When We See Us”

📍 Bozar, Brussels

🗓️ On view until August 10TH

🎨 Featuring over 150 Black artists from Africa and the diaspora

📝 Curated by the late Koyo Kouoh

If you can go, go. Take the train. Take the day. Sit in the middle of it all. And ask yourself not only what you see—but who gets to be seen, and on whose terms